Hilary Mantel (1952-2022)

On the historical record, le juste détail, and the archivist as muse

For a long time, the standard reference point for Hilary Mantel’s fiction was Muriel Spark. Headlines for reviews alluded to the connection (“Spark plug”), or Mantel was said to have “out-Sparked” her predecessor. They were both Catholic writers, concerned with superstition and the supernatural (Beyond Black; Memento Mori, The Bachelors, etc), deft portraitists of London, specialists in comic prose. They wrote about the Middle East – The Mandelbaum Gate, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street. And so on. But there isn’t much to it. Though Mantel’s novel about a hall of residence An Experiment in Love (1995), which won the Hawthornden Prize, bears a striking resemblance to Spark’s portrait of a hostel The Girls of Slender Means (1963), Mantel claimed that she was having intentional “fun” with the comparison, adding that she hadn’t actually “read many of her books.” Her preference was Beryl Bainbridge.

Mantel’s putatively Spark-like books, what might be called the “early, funny stuff,” exhibit a far stronger interest in particulars, the grain of detail, than the abstracted, dynamics-obsessed author of The Driver’s Seat – realist powers that made her such an effective and popular historical novelist, in five books, A Place of Greater Safety (1992), The Giant, O’Brien (1998), and her trilogy about the lawyer and chief minister to Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell: Wolf Hall (2009), Bring Up the Bodies (2012), and The Mirror and the Light (2020). Reflecting on the occasion of Mantel’s death, aged 70, it seems remarkable that during her first decade or so as a novelist, she was so frequently paired with a writer whose only novels set in the past (of the 22 she published) were a pair of autobiographical volumes about the London literary scene in what one narrator called “the middle of the twentieth century.” (There are wartime flashbacks – or, spoiler alert, beyond-the-grave dreams – in The Hothouse By The East River.)

With this mind, there is a British writer, a contemporary of Spark’s, whose work might be more usefully paired with that of Mantel. Penelope Fitzgerald didn’t started publishing fiction until the 1970s, when she was nearly sixty, so she could not have influenced Mantel’s early work. Her forays into what we might recognise as historical fiction (though all her books are set in the past), notably her final novel The Blue Flower, about Germany in the 1790s, came after Mantel had published her own novel about the 1790s, A Place of Greater Safety, which had in any case been started in 1973 (with an earlier version submitted in the late 1970s). The overlap between Fitzgerald and Mantel in general terms is at least as strong as that between Spark and Mantel – they both had Catholic ties (Fitzgerald through her father’s family, the Knoxes), and wrote about the experience of marriage, small English towns in the 1950s, East Anglia, London, the mind-body problem, and the execution of Louis XVI. (For the family in The Blue Flower, it is astonishing news in the Jenaer Allgemeine Zeitung; in A Place of Greater Safety, it is the stuff of daily life.)

Mantel was a Booker Prize judge when The Gate of Angels was on the shortlist, though her own preference was for Bainbridge’s An Awfully Big Adventure – it went to Fitzgerald’s former teaching colleague and Mantel’s admirer, A. S. Byatt, for Possession. Mantel and Fitzgerald were also both contributors to the London Review of Books. In 1995, she wrote to Mantel in praise of An Experiment in Love, adding that her daughter also loved it, and that one day her granddaughter would do too. In 1997, she wrote to congratulate her on the story “Terminus,” which appeared in the LRB in 1997 (it was later collected in The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher). She noted “how moving” the story was, adding “all the more so from the distance, or strangeness, that you’ve put between the narrator and the reader, although we feel brought together by the very last sentence,” in which, following a setback, the narrator reasserts her faith in ghosts and the possibility of communing with them. (The sentence in question: “I am willing, though, to tear up the timetable and take some new routes; and I know I shall find, at some unlikely terminus, a hand that is meant to rest in mine.”) The following year, she begged off sharing a platform with Mantel on the grounds of exhaustion, telling the publicist Karen Duffy: “She is a very good speaker and can manage very well without me.” In one of the countless speaking engagements Mantel took on after the success of Wolf Hall, last year, at Walter Scott’s home at Abbotsford she said that the novel had “changed the game for historical fiction,” and cited The Blue Flower as an influence or precedent. (The first and third volumes in the trilogy won the Scott prize for historical fiction, in 2010 – the inaugural year – and 2021.)

The comparison was made from time to time. Terry Castle places them both in “a great tradition of modern British female storytelling” (though it was a long list – Spark was there too). Wendy Lesser called The Blue Flower a gateway drug to Wolf Hall, though nowadays the opposite might be truer. Whatever the case, it seems fair to say that between them, those novels changed the way historical fiction is viewed – to the degree that admirers have had to say, ‘Yes, yes, it’s historical fiction, but not in that way…’ Lesser said that to saddle A Place of Greater Safety, Wolf Hall, or The Blue Flower with the “hackneyed label” of historical novel was “completely misleading in tone.” James Wood, for example, talking about The Blue Flower, emphasised that “the large amount of historical fact is subtly muffled” and, borrowing a sort of thought experiment about Jewish fiction from Anthony Powell in a piece about the second Cromwell instalment Bring Up the Bodies, asked us to imagine that Mantel had written “a very good modern novel” and then changed the fictional names to English historical figure of the 1520s and 1530s. After quoting a long paragraph in which Cromwell thinks lovingly about his son, Wood asserts: “The historical details in that passage…are not central to its liveliness…it is girded by a cunning universalism, whereby Thomas Cromwell becomes any parent competitively comparing his son with someone else’s; the list of a boy’s possible failings…seems similarly timeless.” There’s no attempt to conceal a fear of the particular historical detail. (The passage goes, in part: “He knows how to bow to foreign diplomats in the manner of their own countries, sits at table without fidgeting or feeding spaniels, can neatly carve and joint any fowl if requested to serve his elders.”)

Wood argues that Mantel “proceeds as if the past five hundred years were a relatively trivial interval in the annals of human motivation.” Mantel would probably have agreed. She believed in psychoanalysis as an explanatory framework. She didn’t see the need for a micro-sociology to explain to a contemporary audience why her characters from the sixteenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries cared about what they cared about. But she had a far greater investment in the historical detail as detail than a sceptic of historical fiction might allow. Mantel went as far as saying that she only “became a novelist because I thought I had missed my chance to become a historian,” and that she only wrote a contemporary novel – as she proceeded to do in the early 1980s, after the rejection of the earlier version of A Place of Greater Safety – as “a way to get a publisher.” Her heart, she said “lay with historical fiction,” and when this was revealed, her approach was avidly and specifically history-minded. Asked about topical resonances, Mantel told a reader: “When I am writing about the 16th century, I actually am writing about it.” (She claimed that no other writer works with her “ideal of fidelity.”) In her novel Fludd (1989), she ridicules a church architect, working on a building called St. Thomas Aquinas, who shows “a Shakespearean sense of history, with a grand contempt of the pitfalls of anachronism”:

“From the Romans to the Hanoverians, it was all the same to him; they wore, no doubt, leather jerkins and iron crowns; they burned witches; their buildings were stone and quaint and cold, their windows were not as our windows; they slapped their thighs and said prithee. Only such a vision could have commanded into being the music-hall medievalism of St. Thomas Aquinas.”

Penelope Fitzgerald used Novalis’s line that novels arise from the shortcomings of history (I presume this refers to history-writing), and Mantel discovered this in her turn. During the late 1970s, she felt she wasn’t “satisfied” with the books she found on the French Revolution. She wanted to read more about the revolutionaries. She started off “guided entirely by the facts” but at a certain point she found that she needed to make things up. She had previously presumed that “all that material was out there, somewhere.” This was how she described her principle:

“I aim to make the fiction flexible so that it bends itself around the facts as we have them. Otherwise I don’t see the point… I suppose if I have a maxim, it is that there isn’t any necessary conflict between good history and good drama. I know that history is not shapely, and I know the truth is often inconvenient and incoherent. It contains all sorts of superfluities. You could cut a much better shape if you were God, but as it is, I think the whole fascination and the skill is in working with those incoherencies.”

Mantel’s concern wasn’t entirely investigative or reconstructive: she was drawn to the French Revolutionary period partly by the similarity to her own experience of repression at school and in health clinics. But she was certainly immersed in the quiddity of periods – historical events as such. A Place of Greater Safety is no allegory. And both Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies were dedicated to Mary Robertson, who before her retirement in 2013 was the William A. Moffett Curator of British Historical Manuscripts at the Hungtinton Library, in San Marino, California. Mantel was influenced by Robertson’s dissertation, “Thomas Cromwell’s Servants: The Ministerial Household in Early Tudor Government and Society,” which was submitted to UCLA in 1975. But even more important was a correspondence she described as “luminous.”

In April 2000, Mantel attended a conference at the Huntington on The Novel in Britain 1950-2000. (The following year, the Huntington started collecting Mantel’s archival papers.) Also in attendance were Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, Christopher Hitchens, Elaine Showalter, Wendy Lesser (whose address concerned Penelope Fitzgerald), John Sutherland, Lindsay Duguid, and James Wood. Mantel read from her second novel Vacant Possession (1986), which concerns the same characters as her debut Every Day is Mother’s Day. While there, she told Sara S. “Sue” Hodson, a curator of literary manuscripts, that she was thinking (as she had been for decades) of writing a novel about Thomas Cromwell. In 2005, when Mantel formally started work on the project, Hodson put Mantel in touch with Mary Robertson. Though Mantel didn’t use the collection, she peppered Robertson with questions about Cromwell’s staff, his travels, his living arrangements, scoping around the possibilities for her fiction.

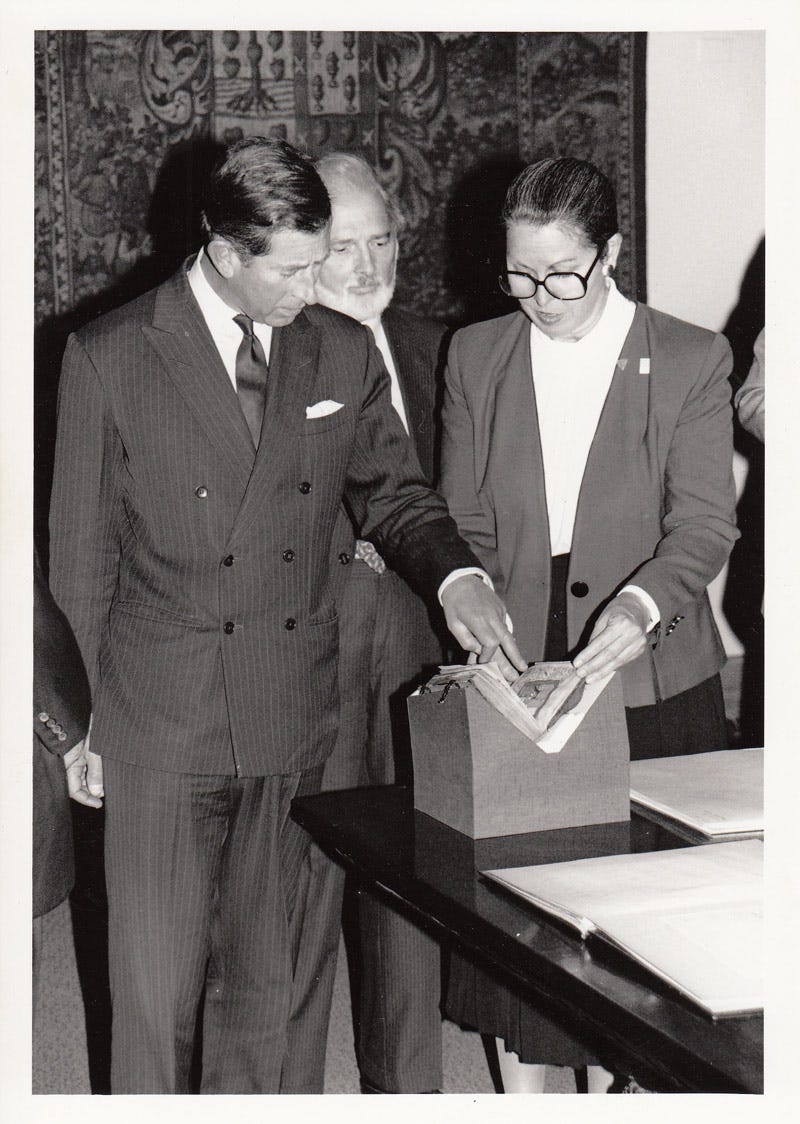

When Wolf Hall received the Man Booker Prize in 2009, Robertson was quoted as saying, “In some ways, it takes a greater skill to work with everything that is known—and from that add your imagination to craft a convincing story—than it does just to make it up.” And when Bring up the Bodies was named on the shortlist in 2012 – it later won – Robertson responded, “Two of my favorite people are honored by this.” It had been Robertson’s belief that Cromwell was not a murderous villain but a deft politician. Mantel said that her aim was to bring together the Cromwell of popular myth with that of academic research of the kind pursued by Robertson. (Mantel visited the Huntington in 2017 for a conference, inspired by her work, on fictional histories and historical fiction, where she appeared in conversation with Robertson and delivered a lecture: https://huntington.org/videos-recorded-programs/hilary-mantel-i-met-man-who-wasnt-there.)

As with her research on the French Revolution, Mantel found herself asking whether something was lost to time, or if she simply didn’t know it yet. And once she solved this query, she would adapt. Her preference was for the existence of the vivid detail – the record as artistic resource. There was more enough embellishment to do without having to imagine events or gestures or rituals. She gave an example of a scene where Cromwell must suddenly and unexpectedly dry ink on a document. In order to write the scene, she felt she must evoke how he would dry the ink. “I couldn’t see what he did, and I needed to see,” she recalled. So she wrote to Mary Robertson, and Robertson “dropped everything.” Mantel recognised that it was “not really an archivist’s concern.” She said that Robertson had by that point became “a very good friend,” and of course she was a co-conspirator, invested in this great serial act of recuperation and vindication. But Mantel used another word to describe Robertson: “muse.” It’s revealing that after finally becoming the kind of writer she always wanted to become, and writing the kind of books that her contemporary comedies only existed to enable, this was the task for which Hilary Mantel would be drawing on quasi-divine inspiration. Here is the resulting passage, from Bring Up the Bodies. Rafe is Cromwell’s chief clerk, Gregory is Cromwell’s son, “he,” of course, is Cromwell:

“Rafe stands in the doorway and does not speak. He looks up at the young man’s face. His hand lets go his quill and ink splashes the paper. He stands up at once, wrapping his furred robe about him as if it will buffer him from what is to come. He says, ‘Gregory?’ and Rafe shakes his head.

Gregory is intact. He did not run a course.

The tournament is interrupted.

It is the king, Rafe says. It is Henry, he is dead.

Ah, he says.

He dries the ink with dust from the box of bone. Blood everywhere, no doubt, he says.

He keeps at hand a gift he was given once, a Turkish dagger made of iron, the sheath engraved with a pattern of sunflowers. Until now he had always thought of it as an ornament, a curio. He tucks it away amongst his garments.”

Magnificent, thank you